Va-yishlaḥ

he kissed him; and they wept

At the end of last week’s parsha, Jacob leaves the home of his uncle Laban triumphant. He has grown into a sophisticated leader and strategist and has accumulated capital and a large family. His mission now, as a fully formed patriarch, is to consolidate an empire on holy land, Canaan, and to cultivate the leader to succeed him. Like the patriarchs who came before him, Jacob is faced with a challenge: How can he turn all that he has built into the Jewish people—a process that requires ruthlessness, even to those he holds dear—while also preserving his family? In Va-yishlaḥ, this week’s parsha, a patriarch learns, for the first time, that he cannot do both at the same time, that he cannot build the Jews out of family ties while also preserving the family itself. It will be Moses who fully grasps this lesson and discovers that the Jews must be formed in a different way.

Jacob’s realization occurs, in three different moments, over the course of his journey back to Canaan: first, his reconciliation with his brother Esau; second, the rape of his daughter Dinah in the city of Shechem; finally, the birth of his son Benjamin.

Twenty years before Va-yishlaḥ begins, Jacob tricks his father Isaac into giving him a blessing intended for Esau, stealing Esau’s right as heir. The last time the two brothers were together, Esau swore that he would kill Jacob. Returning to Canaan, Jacob is uncertain whether his brother still harbors a desire for revenge. Although Esau seems to no longer live in Canaan, his presence nearby, just across the Jordan River, is a danger. If he resolves his conflict with Esau, Jacob can secure Canaan without the threat of Esau’s wrath.

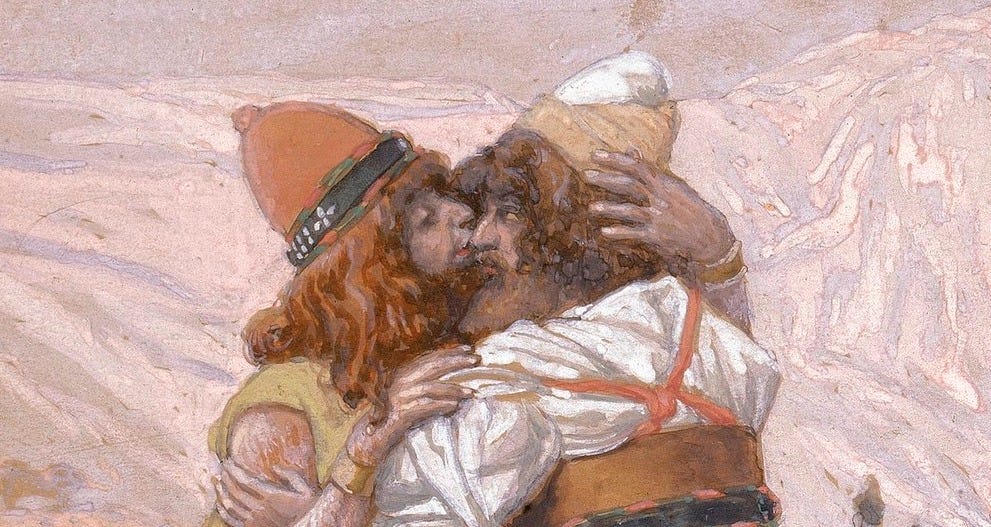

Jacob initiates a reconciliation with Esau by arranging a meeting. In his ruthless, realist fashion, he approaches the reunion as if it were a battle. Jacob splits his troops into two camps. He places his least-valued concubines and sons at the frontlines of his procession, keeping Rachel and Joseph, his favorites, at the very back. But none of this is necessary. Esau, upon seeing his brother after twenty years, gives him a passionate running hug. It seems, for a moment, that Jacob is no longer the cold strategist, but a relieved brother.

He embraced him and, falling on his neck, he kissed him; and they wept. Genesis 33:4

The brothers cry together. Real reconciliation, unsullied by larger political motivations, is a strong possibility. Ironically, Esau, who is often depicted as a barbarian and dangerous, turns out to be a true family man, pushing for reconnection based on family ties, regardless of the challenges that may come. Esau invites Jacob to walk alongside him, back to his home. It’s an offer to walk a path together again, and maybe even to catch up along the way.

But Jacob knows a true reconciliation is not possible. The Edomite path, the path of Esau, has already diverged from that of the Jewish people. Like Abraham with Lot, Jacob knows that too many different tribes with assets on the same land will lead to conflict. Despite Jacob’s clear desire for connection, and Esau’s reciprocation, Jacob deceives Esau again. He tells his brother to go ahead without him, that he will catch up. After Esau leaves, returning to the South, Jacob swiftly moves west, crossing the Jordan and returning to Canaan. Jacob does enough reconciliation to make peace, but not enough to make family. Canaan is gained, but his brother is lost again.

Jacob tries to walk the fine line between familial power and familial love a second time in the Canaanite city of Shechem, where he sets up camp with his two wives, eleven sons, and single daughter, Dinah. When Dinah goes out to visit the women of the city, she is abducted and raped by a prince. The prince professes his love for Dinah, and sends his father, Hamor, to make marriage arrangements with Jacob. Although his sons are outraged, Jacob remains calm and proceeds with the arrangements. The families agree to marriage on the condition that the men of Shechem be circumcised; that way, they can become part of the Jewish people. As the city’s men recover from their circumcisions, Jacob’s sons ambush and slaughter them. Jacob is furious at his sons for making enemies of their neighbors. He insists that their family must now flee. His sons show no remorse. They will not allow their sister to be dishonored. At best, Jacob’s cooperation is an attempt to give Dinah a good life. At least if she is married to the prince, she may retain her honor in the social world and lead a materially comfortable life. At worst, Jacob wants to turn her rape into an opportunity for gaining and consolidating power in Canaan. Jacob’s rage at his sons stems from the realization that he has taught his sons the skills of trickery, contract, and war, but not the ultimate purpose for using those skills. They have learned from him everything but the Godly mission of building the Jewish people and a home for them. Jacob’s sons misconstrue his larger political project of consolidating familial power as a more simple, personal project: to preserve the private family above all else. As was true of his dealing with Esau, Jacob has failed to align the two projects—preserving the family, building the Jewish people—and he flees.

While traveling, Rachel dies giving birth to Jacob’s youngest son. With her last breath she names her son Ben-Oni, or “child of pain.” Jacob, however, overrides Rachel’s decision, naming the son Benjamin, “child of strength.” Consistently in the Torah, children’s birth names carry the weight of their parents’ hopes, actions, and tragedies. Name changes, as in the case of Abraham and Sarah, signify an exit from those parental stories and an entry into the Godly mission of building the Jewish people. Jacob’s birth name, and subsequent name change to Israel, is another such instance of exit and entrance.

By changing Benjamin’s name from the very beginning, Jacob has spared his son from the lifelong burden of somehow being responsible for or associated with his mother’s death. Jacob shields Benjamin from the weight of that personal tragedy. At the same time, he is doing something else. He has chosen not to load Benjamin and his name with his own hopes and goals. Often in the Bible, the successful patriarch, working with or through God, chooses his youngest, rather than his oldest, son as his favorite and his successor. But Jacob doesn’t do that to Benjamin. Instead, he chooses Joseph as his favorite and his successor. In not choosing Benjamin, and in changing his name, Jacob frees him from expectation entirely.

Out of the three moments in Jacob’s journey home—the reconciliation with Esau, the rape of Dinah, and the birth and renaming of Benjamin—the last is the most significant. It’s the odd one out, the only time that Jacob allows himself to shed the responsibility of ruthless realism. By freeing Benjamin from his mother’s death and his father’s favor, Jacob acts as a father, not a patriarch. Joseph will go on as the next people-builder, not Benjamin.

But the patriarchal line ends with Jacob. It does not truly carry on with Joseph; after all, we don’t know much of Joseph’s marriages and children. We know Joseph because he leads his family of origin into Egypt, where they will ultimately become enslaved. Why, then, doesn’t Joseph become a true patriarch, as Jacob and Abraham were? Maybe it’s because Jacob, in the act of renaming Benjamin and freeing him from his mother’s tragedy and his father’s expectations, is the first to realize that the Jewish people cannot be built out of a family.

Families are spaces of favoritism, jealousy, and trauma. There will be too many siblings, too many tribes, too many interests, and not enough physical space or love from a parent to go around. In such an environment, resentment, betrayal, and fission are inevitable.

There must be a new model for people-building, a new model that Joseph will set into motion by bringing the Jews into Egypt and that Moses will complete in leading them out. This new Jewish people will be built not upon family ties but upon a shared history of enslavement and oppression, a shared experience of struggle, and a shared ethic. Jacob does not quite see this, but after seeing how difficult it is to build a people from a family, he allows himself the freedom to be a true father—and a true son. It is only after his tender grant of freedom to Benjamin that he can finally see his father Isaac, whom he has consistently avoided thus far, again.

And Jacob came to his father Isaac at Mamre, at Kiriath-arba—now Hebron—where Abraham and Isaac had sojourned. Isaac was a hundred and eighty years old when he breathed his last and died. He was gathered to his kin in ripe old age; and he was buried by his sons Esau and Jacob. Genesis 35:27-35:29

Image: Tissot’s “The Meeting of Esau and Jacob”